We Care About YOU! harm reduction history at the leather bar

History, of course, follows us to the doctor, and the best medical care is sometimes found at the bar.

A few weeks ago I wrote in this newsletter that I’d report soon from my visit to the Donny’s archive (for those of you just catching up, Donny’s Place and Leather Central is a wonderfully cheap and tacky, deadly serious leather bar that Donald Thinnes has been operating in Pittsburgh’s Polish Hill neighborhood under slightly different names almost continuously since 1973) at the Heinz History Center. Instead, I got depressed and tired. I’m a trans person with an hourly day job and have spent a lot of time lately proving myself to doctors. It’s not all sucking dicks and having ecstatic encounters with history over here. But history, of course, follows us to the doctor, and the best medical care is sometimes found at the bar.

Today I’m writing after having gotten into a fight over the phone with the nonbinary doctor who prescribes my hormones, but whose primary work is acting as CEO for Western Pennsylvania’s only independent abortion clinic. When I asked them what they were looking for in a blood test that would determine whether or not they were willing to renew my testosterone prescription, they responded to my questions not with information but by telling me that they were stressed, that they did not appreciate my tone, that another doctor would have dropped me long ago, and that I was welcome to find care someplace else. It’s pretty thrilling, frankly, after a lifetime of appeasement to say NO one time and to have things blow up just as I always suspected. What TERFS and doctors call roid rage is just what happens when a person quits passing emotionally as a white cis woman, and starts saying what they mean instead.

After I pushed a little more, the they/them abortion doctor let slip that they couldn’t risk refilling my testosterone prescription until the test results came in because they feel precarious, presumably under increased scrutiny since the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Which, fine! I’m not trying to put the abortion clinic in danger! But don’t take that shit out on me, or try to suggest that it’s inappropriate for me to ask questions about the decisions my doctor is making on behalf of my body. Unless autonomy and choice are only for cis women, not that anyone but the state is cis anyway [1].

In the afternoon I texted my friends, who hooked me up with clean needles and a vial of testosterone to float me until I again have direct access to a medical supply. Testosterone, like diazepam, Hydrocodone, mescaline, and psylocibin, is classified as a Schedule III drug, which I mention because this kind of supply sharing and survival work (getting the meds you need whether or not the official channels will provide them) is drug user knowledge, and intravenous drug users were among the first in the US to be impacted by HIV/AIDS.

In her furious and thorough tome Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT-UP, 1987-1993, Sarah Schulman describes how the disease which would come to be called GRID and then HIV/AIDS was known among injection drug users in New York City as early as the 1960s, long before it was acknowledged by medical providers or, god forbid, the National Institutes of Health. I’m thinking about this because one of my favorite things that I learned in the Donny’s archive was that Pittsburgh’s rich, connected network of gay bars and after-hours clubs, the Tavern Guild organized by Robert “Lucky” Johns in collaboration with the mob, was one of the main reasons that gay men in Pittsburgh were able to access early treatment for and information about AIDS, and not because the government swooped in. It was because they got drunk together and sucked each other’s dicks, because they worked with organized crime to ensure relatively safe and stable access to social and sexual gathering places, because they grieved their loved ones together as the virus spread, and so to some degree they knew and trusted each other. While “many gay bar owners in Philadelphia believed that handing out AIDS literature would drive away customers” according to the Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh’s small-town feeling made a different level of care possible in the bars.

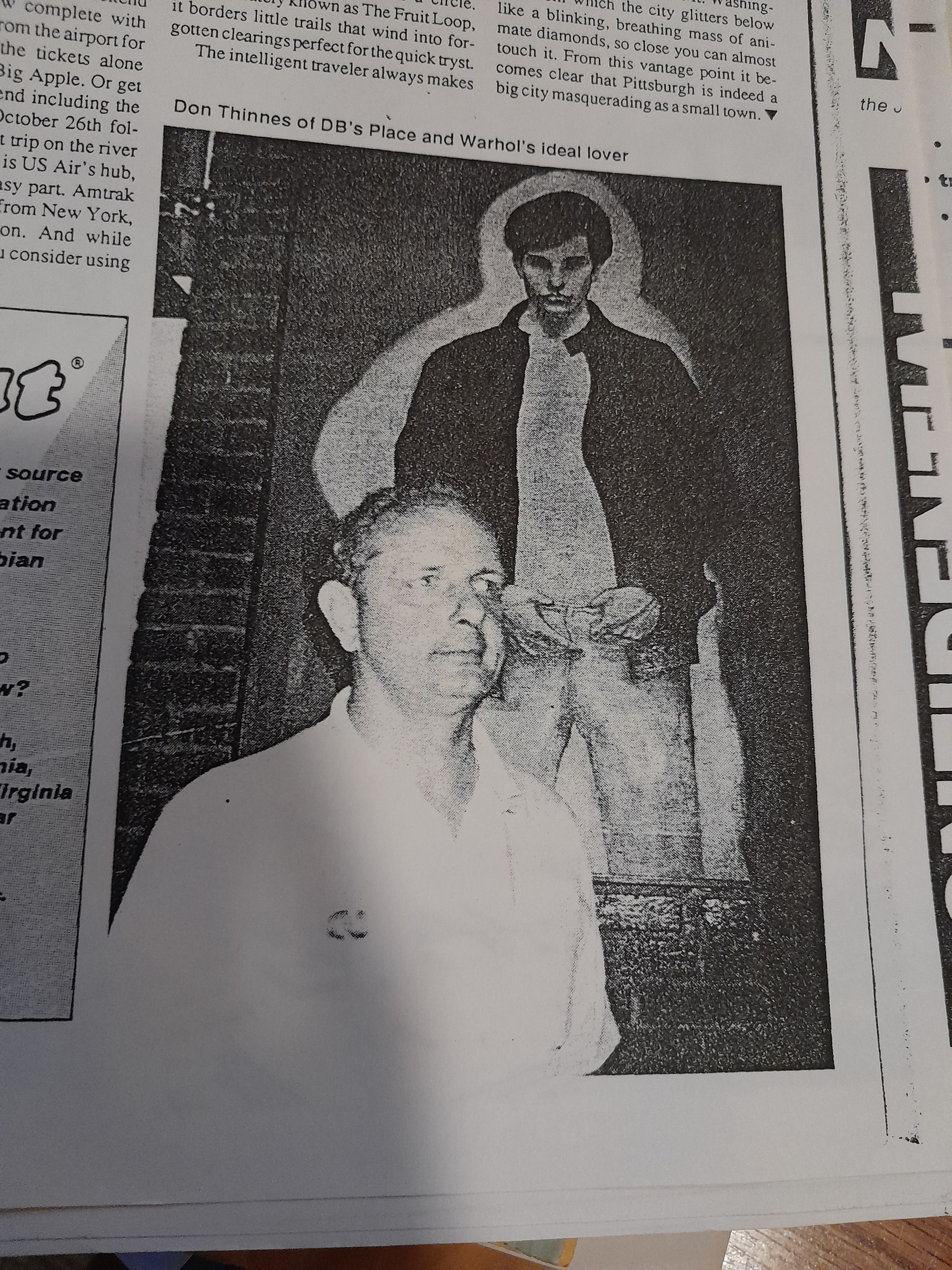

To illustrate what I mean, here’s an excerpt from that same undated Pittsburgh Press article, a clipping from which was carefully folded in Donald Thinnes’ papers, with this section circled:

Obviously everyone is worried about their business,” said Bill Kaelin, an executive board member of the Norreh Social Club [which would later be called Donny’s] in Polish Hill. “But if you have a problem that’s attacking your customers, you have to deal with it.

Others gave away condoms or sold them in cigarette machines. “When I ran out, said Don Thinnes, a guild board member, they (the customers) wanted to know where the hell they were.

An early 2000s article in Pittsburgh’s local gay paper, Out, gave a survey of the city’s thriving nightlife scene. Here’s what Chuck Honse [2], a member of the Tavern Guild who, with his partner Chuck Tierney, ran the now-closed gay bars New York, New York [3]; Images [4]; and Holiday [5], had to say about Pittsburgh’s early response to AIDS:

[Honse] recounts that the National Institutes of Health chose the University of Pittsburgh for the famous Pittmen study in which, as early as 1984, 5,000 men had blood work done. (The Tavern Guild gave free drinks to those who gave blood; beats orange juice.) Consequently, AIDS education was widespread and early. As a result, the gay population of Pittsburgh has one of the lowest positive rates in the country.

A later City Paper article covering the 2007 closure of Holiday notes that the bar “offered a free drink to those who signed up for Pitt's Men's Study, a large, federally funded investigation into the epidemic that began in 1983. There was even AIDS blood-testing in the bar's basement.”[6]

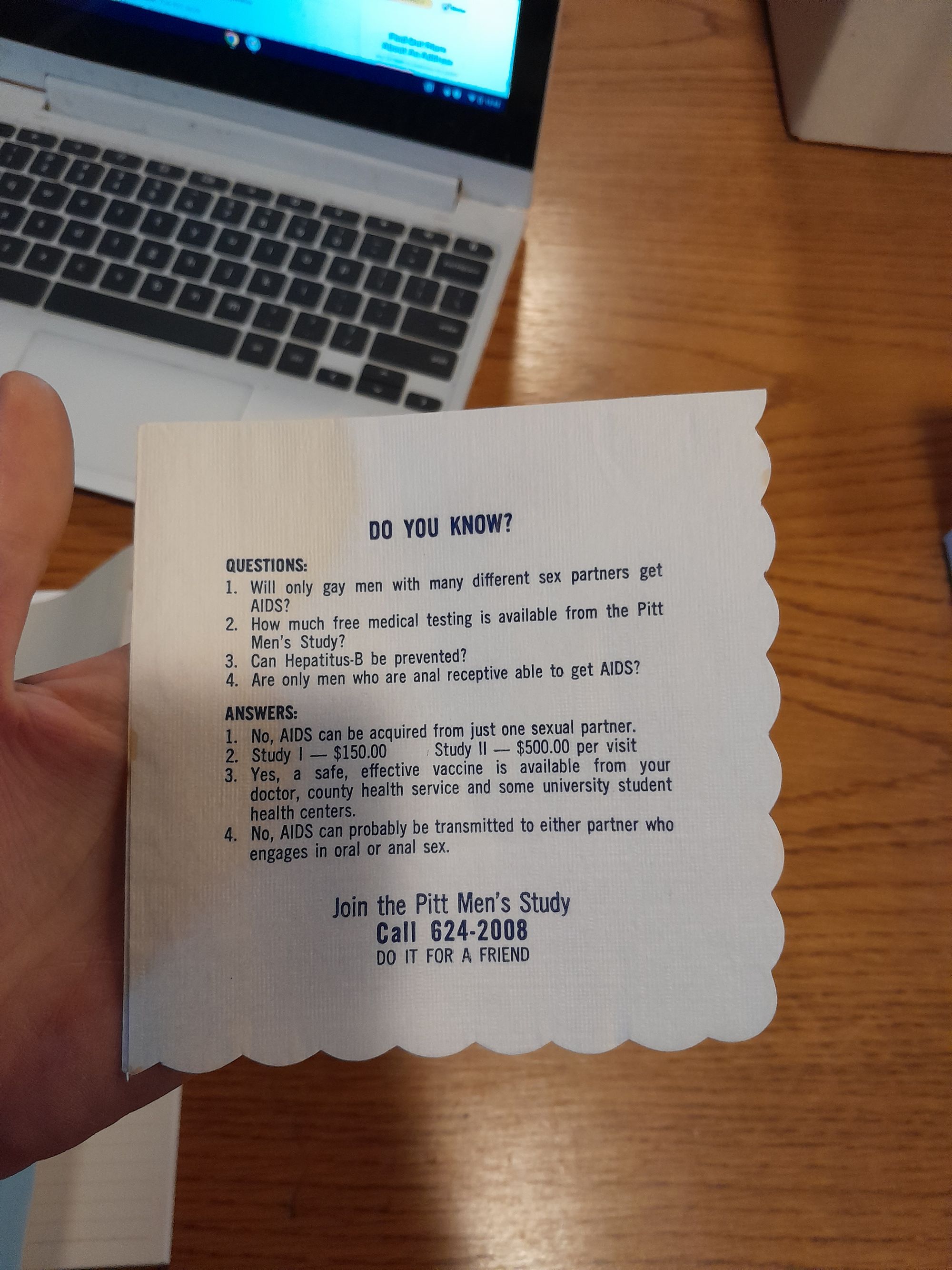

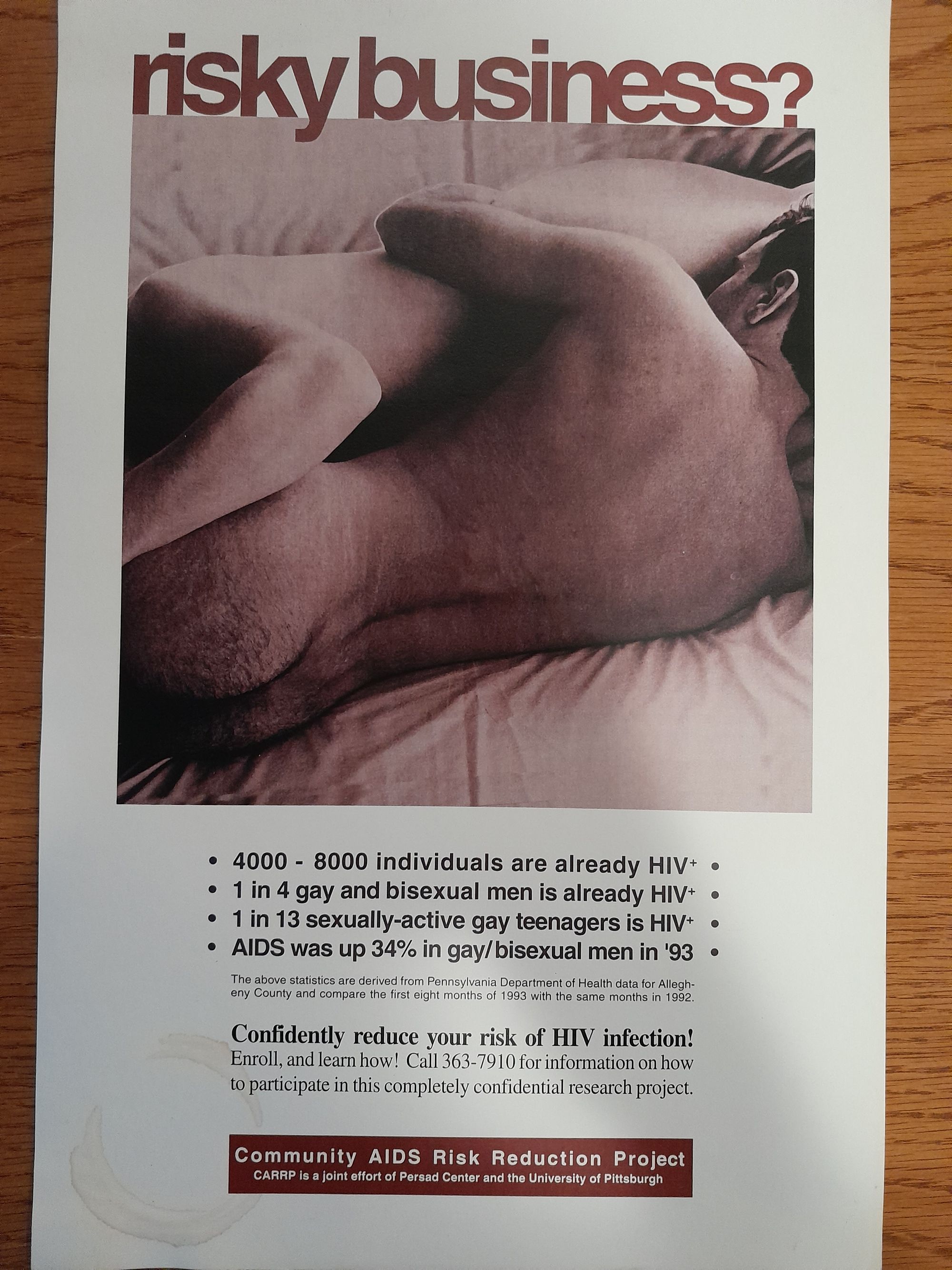

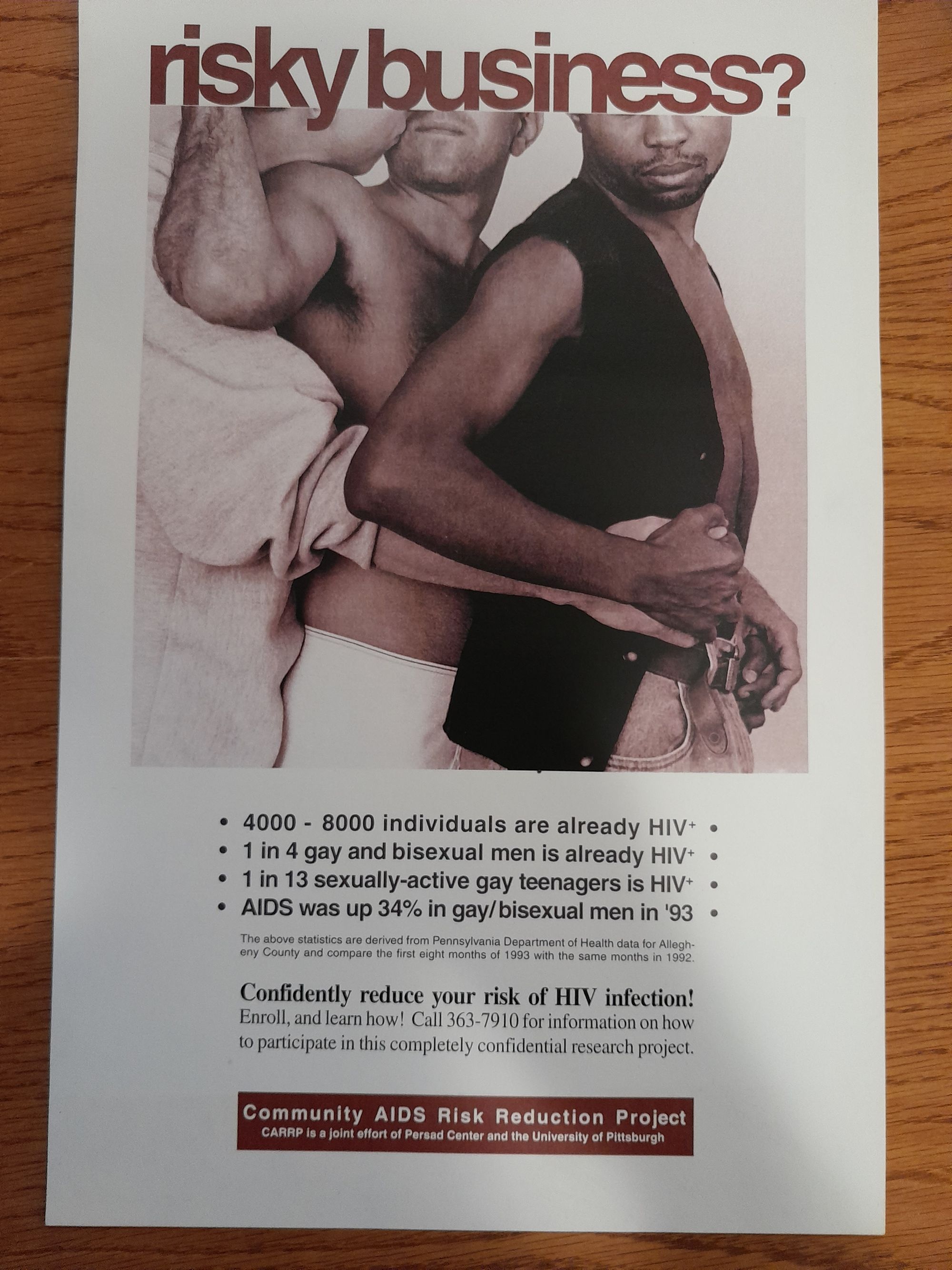

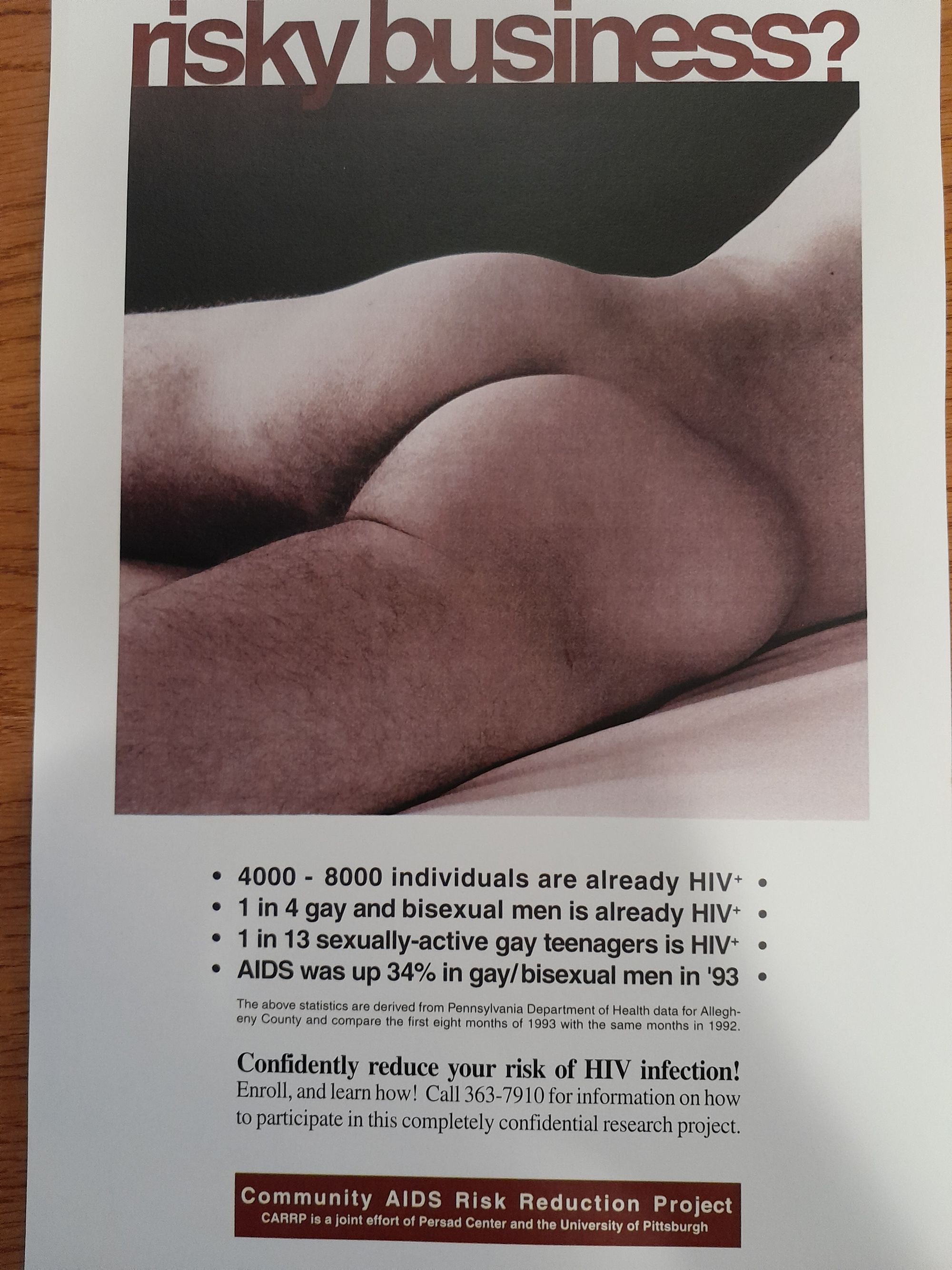

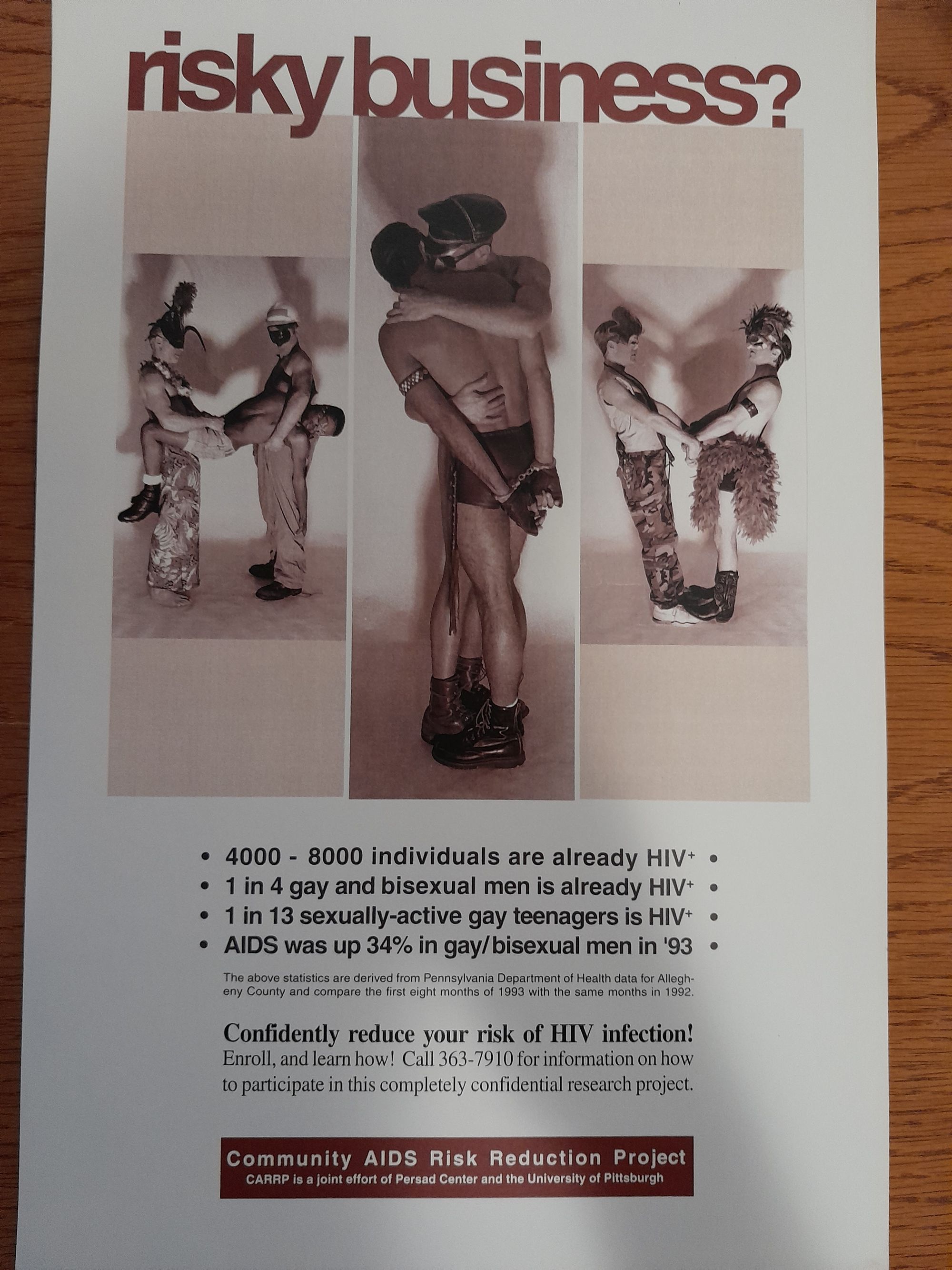

That’s just the tip of the archival iceberg. Donald Thinnes’ papers are full of ephemera relating to the study, which is ongoing. Highlights include study-produced bar napkins printed with facts about HIV/AIDS rates in Allegheny County; a series of posters advertising the Community Aids Risk Reduction Project depicting gay men of various ages and races having threesomes, entwined in bed, and participating in a variety of leather dynamics; a 1995 newsletter with the heading Thirteen Years of HIV Research and You Are There complete with timeline; and informational pamphlets with such titles as Man to Man, AIDS and IV Drug Users, and All About AIDS.

In the year 2000, the Allegheny County Health Department issued the Pittsburgh Tavern Guild a certificate of merit in public health “for outstanding service to the citizens of Allegheny County in the recent outbreak of Hepatitis A.”

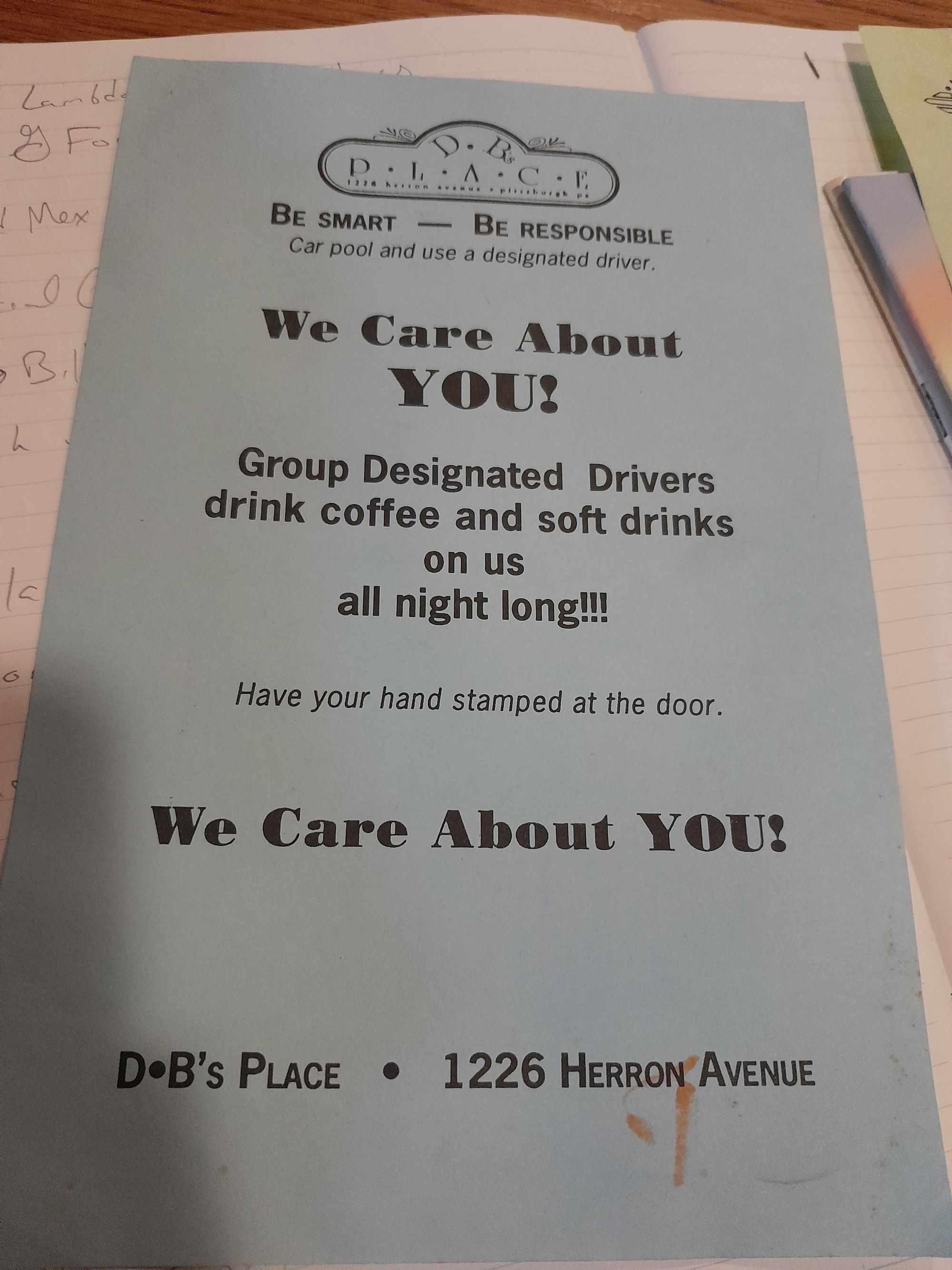

The Thinnes archive also contains flyers like this one, which advertises free coffee and soft drinks all night long for designated drivers: We Care About YOU! Unlike when a doctor says it, at the gay bar I sometimes believe it [7].

Even having just encountered all this evidence of harm reduction approaches in Thinnes’ archive, I was naive, a little surprised to learn last Thursday from Lexi, a straight cis woman in her late sixties or early seventies who’s been working in Pittsburgh gay bars since 1982 and who is currently the Friday-night bouncer at 5801 (“I don’t know why, I just know gay bars are where I needed to spend my life! Excuse me, that’s my lesbo calling. We’re best friends. I call her my lesbo wife and she calls me her straight wife. I’m making a warm bacon dressing for us tonight. Do you know about the [AIDS] quilt?”--and her relief that I did) that Donny’s, then known as the Norreh Social Club, closed its back room 1983 or ‘84 due to the AIDS crisis.

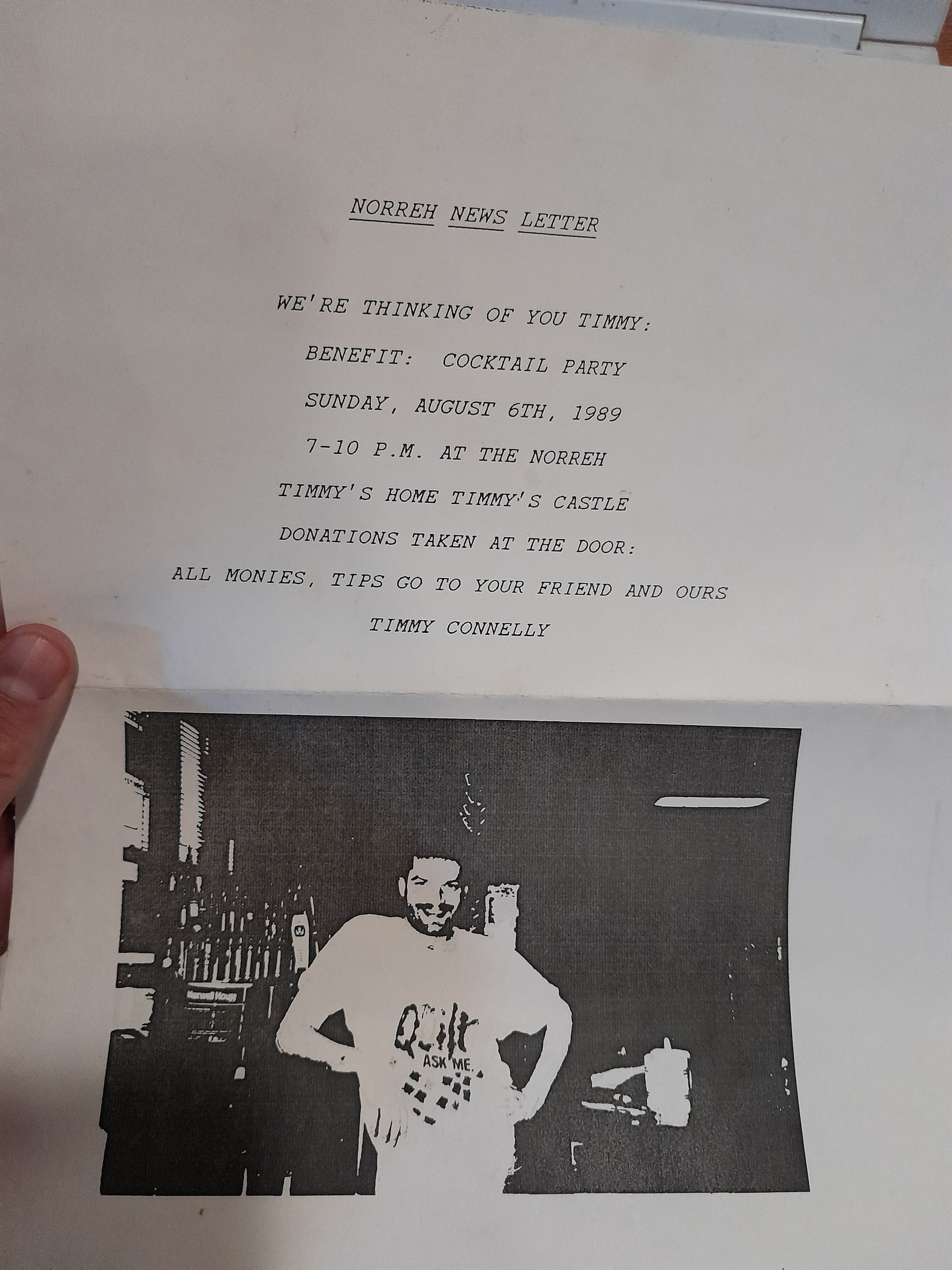

How to hold all that grief, how to take pleasure and also to take care of each other? People in 1984 were still fucking even if they didn’t do it at Donny’s, which in 1989 was hosting fundraisers for friends who were sick.

In 2020 the New York City Health Department recommended glory holes as a safer sex measure to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID. As readers of this newsletter will remember, the booths and back room at Donny’s are currently open; they were already in May of 2021, when I first ventured back into public with my crisp new COVID vaccine [8]. I don’t yet know how long during COVID Donny’s was closed for, if at all, nor when during the AIDS crisis the back room reopened, and I wonder how much of its initial closure had to do with health concerns, how much with fear and grief, and how much to do with the fact that gay sex–and intravenous drug use, and sex work–was and often still is highly criminalized under the guise of public health. (I wonder also if that kind of pressure and fear of scrutiny is something the abortion doctor might relate to.) I wonder what would be different if older-guard gay bars like Donny's distributed masks the way they once handed out condoms and rewarded a blood test.

I’ll write more about the Youngstown leather bar The Mineshaft in a future issue of this newsletter, but it’s worth noting for now that that that bar, which has on the whole an older and sparser clientele than Donny’s, closed its back room at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as if this writing has not reopened the booths. Sex isn’t the only reason to go to the leather bar, and we know abstinence-only education doesn’t work. People die from diseases, and they also die from loneliness.

In his brief and brilliant book Trans Care, Hil Malatino writes,

"This queer and trans care web has no center, but in some significant ways it has emerged because of the way the normative and presumed centers of a life have fallen out, or never were accessible to or desired by us in the first place. So many estranged and tangential relationships to birth or adoptive families, skepticism and proverbial allergies to normative familial structures, interpersonal, institutional, and professional shunning, exclusion, and ostracism. This is not the only synopsis I could provide—there’s plenty of joy. But it would be foolish to deny that some of what binds us to one another is directly tied to the affective and practical disinvestment of the people and institutions we’ve needed—or been forced—to rely upon for survival. We have learned to care for one another in the aftermath of these refusals."

Other trans people are the ones who told me about Harry Benjamin, the German endocrinologist and sexologist who is responsible for the WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health, formerly known as the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association) standards and for much of early American trans medical care, was invested in erecting barriers to make sure that as few people as possible transitioned, and that those who did conformed as closely as possible to cis standards of gender and sex–which many cis people fail at anyway. No doctor ever explained this to me. It’s because of other trans people that I was able to push back on the abortion doctor who tried citing those standards as a way to end our argument, why I canceled my appointment with a surgeon whose followup concerns started and ended with convincing me to get photorealistic tattoos of nipples on my newly flat chest.

The reason I’m managing to write this newsletter today after weeks of feeling stuck is because my important friend Sam has COVID right now and demanded I send them something to read while they’re home sick. The other night I had a drink with a friend of a friend who I met at a wedding in Minneapolis; she’s a medical resident, not trans, who studies the somatic experiences of trans people after surgeries, and was pretty frank with me that the reason she studies us is that we seem to know how to take care of each other and ourselves better than medical school was showing her how to–not in terms of medicalized transness even, I mean she was shocked that I was sharing my life with my loved ones, letting them see me.

I don't mean to be pessimistic about medicine. Like intimacy, it's necessary and imperfect and sometimes excruciating. But when it works, when doctors act from a perspective that takes their patients' experiences and real lives into meaningful account, it can be beautiful. In the Spring 1998 edition of the Pitt Men's Study newsletter, clinic coordinator Bill Buchanan reported that "Deaths from AIDS were down 44% in the first half of 1997, and the number of new AIDS cases has dropped 12%. I've seen some startling and impressive changes both in men who've been infected for years and in men just recently infected." But what really moved me was the final line of the next paragraph. "The data for this groundbreaking study," Buchanan writes, "came from our freezers and database, that is from our men." Our men. Each other's. How else could it be?

- Not that there are cis women! As Jules Gill-Peterson would say, only the state can be cis: https://sadbrowngirl.substack.com/p/the-cis-state

- whose last name is spelled Honce in the Out article, but with an s in every other source I could find

- A piano bar and restaurant which operated in the spot that is now 5801 Video Lounge & Bar, at 5801 Ellsworth

- 985 Liberty Avenue, notoriously divey, formerly known as Auntie Mame’s, which closed in 2019 after being condemned in July of that year when a piece of wall from the fifth floor fell onto a neighboring building

- which Robert Johns opened in Oakland, at 4620 Forbes Avenue in 1968; Honce purchased it in 1977 and ran it with his partner Chuck Tierney until the bar closed in 2007, when CMU, which offered the Chucks an undisclosed and reportedly unrefusable amount of money for the building, knocked it down

- https://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/last-holiday/Content?oid=1335090

- Briefly, a shoutout to my favorite opulent but not especially gay North Side dive bar Riggs for the working breathalyzer hanging on the wall among the tchotchkes, a decoration that’s available for anyone to use before departure.

- That same month, the bathhouse Club Pittsburgh stopped requiring mask-wearing for fully vaccinated club-goers. In March of 2021 the arcade was open at the adult bookstore in McKeesport, which had closed only for two weeks at the very beginning of the pandemic.