adventures in yiddishland

Perhaps I was trying to cruise Yiddish itself.

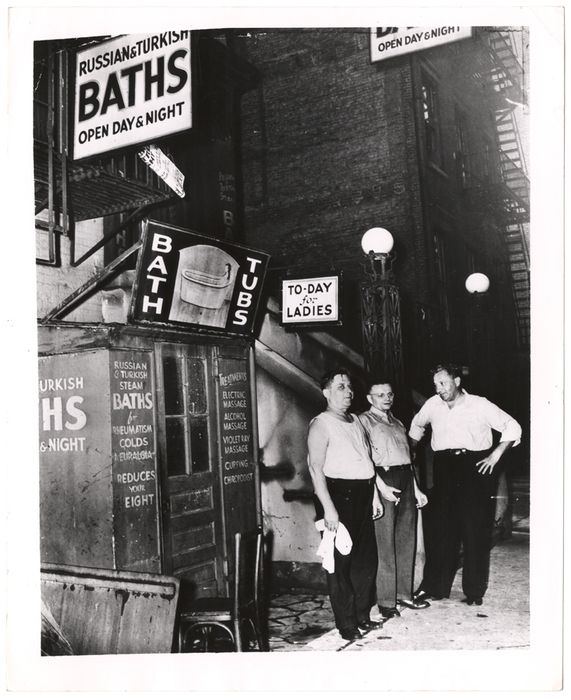

The Russian & Turkish Baths on East Tenth Street in Manhattan is a place where people really do go to use the facilities. It was also the first bathhouse I ever visited, and the first place I ever cruised, though I didn’t go with that intention in mind, and I don’t think I yet had the language to describe what happened. The year was 2012 or 2013. It can’t have been a Thursday or a Sunday, days which were reserved for men, and the number of Hasidim who were there tells me it wasn’t shabes either. Let’s say it was a Friday, or maybe a Wednesday. It could have been early in the week but I doubt it. I was more or less a woman at the time.

The bathhouse, situated in the basement of a worn, late nineteenth century tenement building between First Avenue and Avenue A in the Lower East Side first came to my attention through a network of Yiddishists, people in their twenties and thirties who like me were devoting themselves to a life in Yiddish, or at least to Yiddishkeit–a sense of Jewishness and a dedication to Yiddish language, literature, history, and culture that suffused their–our–days with purpose and pleasure. At the time of my visit to the baths I was three years into my romance with Yiddish, and it was a romance upon which my cynicism had not yet intruded. I was studying Yiddish in college, but it wasn’t just that; I was learning how to live in a network of Yiddishists all over the world, experiencing a new kind of belonging predicated on choice and affinity and devotion to this very small, largely impractical language. At the time, mainstream Ashkenazi and white American Jewish thought supposed that Yiddish was dead, that it had died in the Holocaust, and that the State of Israel and Modern Hebrew were the animating forces of contemporary Jewish life, and particularly of any Jewish future.

I knew this to be untrue. I knew I didn’t want a Jewish future based in reactive eugenics, that aimed to replace murdered Jews with live ones through biological reproduction, nuclear families, allegiance to whiteness, and a militarized erasure of Palestinian life, of Arab Jewishness, and of Black and brown Jews. I didn’t want a nation-state, but I did want places where I could go to feel Jewish, and especially to feel Yiddish, to live in the present and also feel a sense of history. Brooklyn was full of Hasidim living whole lives in Yiddish. My friends and I weren’t dead. Yiddish couldn’t be either.

I had just learned two very important terms. The first, doikayt, is a Yiddish word which means here-ness and which comes out of the tradition of Jewish socialist organizing–the Labor Bund–in the Russian Empire and Poland that was active from the late nineteenth century until World War II. Jewish socialists, opposed to Zionism, believed that Jewish life could and should happen wherever Jews already lived. The second word was Yiddishland (or, rendered in YIVO-standard transliteration, yidishland), a neologism that seems to have emerged among Yiddish writers during the same period that the Bund was staking a claim for Jewish places without Jewish nationalism. According to the Yiddish literary scholar Benjamin Harshav in his book Language in Time of Revolution, Yiddishland was a way to talk about “the sense of a surrogate homeland their language provided Yiddish writers and readers.” In his 2006 book Adventures in Yiddishland, the scholar of queer and Yiddish Studies Jeffrey Shandler coined the term postvernacular to describe the kind of Yiddish I spoke, more as a signifier of belonging, of certain cultural and political orientations, than as a tool of everyday life.

Even to native speakers, Yiddish is not only a language, it’s also a taste, an inflection, a sensibility, but of course it most demands description when threatened. (Ask me about the Yiddish Studies scholars I know who won't say in public how much grief they feel about the Holocaust because publicly they must profess that Yiddish is a living thing, as if death doesn't mark those of us who survive it.) Anyway, Yiddish had me and the baths had Yiddish. When I lived in New York I spent much of my free time walking: around the Lower East Side of Manhattan, identifying buildings where various Yiddish poets had lived, and where certain matzah factories had operated, a hundred years prior; or else through Borough Park and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, practicing my Yiddish by reading signs and eavesdropping on conversations, though my YIVO-standard-trained ear struggled some with the Hungarian accent of Satmar Yiddish spoken by people who were fluent, and who had learned Yiddish at home, unlike me.

Which is to say that perhaps I was trying to cruise Yiddish itself.[1]

At any rate I was hungry for places where I could plunge my whole body into Yiddish, where Yiddish wasn’t just something I could look at, or listen to, or even taste. I knew about B&H Dairy Lunch on First Avenue, about the walking tours of the Lower East Side that took tourists as I once had been to Yonah Schimmel’s knishes on Houston, to the Pickle Guys on Orchard Street, and to Kossar’s Bialys on Grand, shops I returned to over and over again, so often that the Pickle Guys came to recognize me, and often gave me something experimental to taste alongside the single kosher dill or half sour I’d buy before walking over the Williamsburg Bridge.

****

At the baths, it was me who could get brined, not the pickle. The Tenth Street Baths, as it was first called, was established in 1892 and, like most public baths in New York City, was initially intended to give recent immigrants–mostly Ashkenazi, Italian, Irish, and Chinese–a place to bathe, since their crowded tenement apartments often lacked hot water. While crucial, these efforts at public hygiene also carried a condescending and assimilating moral tone, as white Christian women social workers believed that that the pungent, garlicky foods the immigrants ate rendered their bodies odorous and unclean, and that the spread of disease in these unmanageably crowded apartments was the immigrants’ own fault.

But in the twentieth century, the Tenth Street Baths became a beloved, if crumbling, men’s club. Its primary clientele was Jewish, and in the basement of the tenement building on East Tenth Street the European Jewish tradition of the schvitz, a sweat for health, companionship, and pleasure, was kept very much alive. People cared about the baths, and treasured their time there, aware that this way of life was fleeting and perhaps unrecoverable if lost. As early as 1984, amidst citywide closures of bathhouses as a preventative measure against the transmission of HIV and AIDS, the New York Times ran an article noting that the Russian-Turkish Tenth Street Baths was the last of its kind in the five boroughs. In the article one bathgoer, concerned about the threat of closure, expressed his allegiance to ''This [...] Old World kinda place [...] where men are men,'' going on to tell the reporter that “he doesn't need doctors, either, or marriage counselors or fancy-schmancy health clubs or men's clubs - ''just as long as we have the schvitz.'' The owner of the baths at the time, Tim Hunter, tells the Times reporter “The Jewish population moved out of the Lower East Side. The younger generation looked upon the schvitz, brought here by their ancestors from the old country, as too old-fashioned. Most of the baths in the city took on sexual connotations.''

Other Times coverage indicates that mafia members also made up so significant a portion of the baths’ clientele that deaf massage therapists were sought out and given priority in hiring so that the mafiosos could conduct business at the baths without fear of being overheard.[3] And while Hunter is on-record denying any gay sexual activity at the baths on Tenth Street, the phrase no homo usually indicates the presence of a homosexuality which must be denied.[4]

***

In the opening chapter of his new book Koshersoul, Michael Twitty writes

The most imperative Jewish word to me is mishpocheh [...] It’s Yiddish, and just so you know, I’m not being too Ashkenormative. The Hebrew is mishpachah, and for centuries it has meant family, tribe, clan. Deeper than that it means family beyond blood or boundaries or even centuries. A closely related word is “landsman,” the connotation being that someone is from your same town or point of origin, but the gloss of which means “kinsman,” someone who comes from what you know and are [...] When you’re Black and Southern, the word is “kinfolk.” The first question I ask someone who is an African American landsman is, “Where your people from?” That way, I know that a fellow landsman is mishpocheh. [...] When you’re gay, the word “family” is code for being a fellow “queer person.”

Family is no separate thing, not sterile and respectable, nor bound by biology.

When I visited the baths I found an atmosphere that was at once esoteric, erotic, and profoundly familial. The establishment is owned by two Russian Jews, Boris Tuberman and David Shapiro, who bought the baths from Tim Hunter in 1985 when they were in danger of closure due to New York City’s crackdown on public sex during the AIDS crisis, and have alternated weeks of operation since the unraveling of their business partnership just over a decade later. According to a pleasurably acerbic 1997 Wall Street Journal article:

In 1992, Mr. Tuberman and Mr. Shapiro broke up. A notice appeared on the lockers. "The bath," it said, "is operated by separate owners on alternative weeks." No kidding. Every Monday morning, one complete Russian staff -- around 15 people -- replaces the other complete Russian staff, and the whole shebang changes hands.

"We don't have merchandise, only hot water and steam," reasons Mr. Shapiro. "We get the bills, we split them in half, down the middle." It works. The baths improve, improve, improve.

In 2016, the New York Times ran an article which observed that “[t]he fabled baths — housed in a tenement basement and frequented by Frank Sinatra and John Belushi — have been claimed by the denizens of the new New York, as shvitzing has joined shuffleboard, brewing beer and pickling as a pastime enjoyed by millennials as well as retirees.” The preceding paragraph of the article describes a bathhouse full of young (straight, white, Christian) people with defined abs discussing their Tinder dates in a place where soft stomachs and hard protruding bellies once predominated Even the 1997 WSJ article mentions that the baths have become “straighter,” though it doesn’t indicate how gay they were before or during the height of the AIDS crisis. Both the 1997 WSJ article and the 2016 NYT article indicate that bathhouse culture is getting whiter and straighter and more Christian. Gay and Ashkenazi cultural practices are desirable in the mainstream because they offer a connection to a cultural specificity and community sensibility that is absent in the clean, vacuous buildings and lives that gentrification facilitates.

Bathhouse culture is gay culture, and Jewish culture. While white Christian nuclear family culture is concerned with sterility and hygiene, bathing, broadly speaking, is ethnic and raced. I think about how New York City’s public baths were first established so that immigrants and poor people in the late nineteenth century had somewhere to wash, and about how Jews survived the Black Plague largely due to regular hand-washing, a ritual and hygiene practice unfamiliar to European Christians, and I think about Black Twitter talking about how white people don’t wash their legs.

***

On further reflection, my visit to the baths must have been in 2012, because I still had a boyfriend and because it was before Simon Rich’s short story “Sell Out,” on which the 2020 Seth Rogen film American Pickle was based, appeared in the New Yorker, making visible the potency of bourgeois millennial Ashkenazi longing for an evaporating Yiddish past–by which of course I mean blowing up my spot.

Anyway, what I remember from my visit is a group of older men–definitely Russian, possibly Jewish–sitting at the restaurant across from the welcome desk of the bathhouse, drinking vodka out of tiny glasses and eating rolls of roll mops with their hands, talking and laughing. I remember having the impression that the men resented our presence–I came with a friend, who also believed themself to be a woman at the time–because with women at the baths the men too had to wear shorts, rather than simply going nude or wrapping a towel around their waists, though I don’t recall how I knew this. The men drinking vodka wore towels around their waists anyway. They glared at us when we came in, or else I imagined it.

In an ordinary transmasculine way that I didn’t yet understand, I envied those men, the freedom I imagined them to have in their bodies. I wanted to sit in such a state of undress, to pull pickled herring off toothpicks with my teeth, but not in the body I had.

Downstairs, amidst the slap of wet feet on concrete floors, the sharper slice of wet oak leaves onto bare backs out of view, the air hazy with steam, I wandered into the sauna. I think I remember one straight couple, a blowjob, the rest of us sitting delicately still, but I’m not sure. Eventually I walked back out into the atrium, where I spotted the man whose name I never learned standing at the edge of the heated pool. He was one of several Hasidic men at the baths that day, but the only one to make eye contact with me.

I approached him first, speaking Yiddish to indicate that I understood it was forbidden for him to be here, on mixed-gender day, looking at bodies like mine. I must have been wearing little synthetic shorts, issued by the baths, and a sports bra. I don’t remember feeling sexy, but I do recall feel profoundly exposed.

I think the dissonance–fine, call it dysphoria, though that word’s connotation is too narrow for my meaning–that I was experiencing is part of what drew me to the Hasid as well. I knew his body didn’t belong here either, because his peyes and accent indicated that he observed a practice of tsnius, or modesty, which would prevent him from being among women other than his wife in such a state of undress. Did he have a wife? I asked. Of course he did. I think.

It’s not that I disapproved of his choice to visit the baths on mixed gender day at all. Rather, I admired the shared code of privacy that was implicit among the Hasidic men who were there; they all were witnessing one another transgress the expectations of their community, and with that mutual witnessing came a mutual promise to keep one another’s secrets. Because I also understood but was not of his context, because he and I each had something the other wanted, he and I had a frisson, a sudden intimacy with one another, as well.

So here’s what happened. When it became clear, standing on the tiled walkway between the hot pool and the cold plunge, that I spoke Yiddish too, he asked me why (I had studied it) and if I was also Jewish (Yes). He wanted to know, then, if I had a boyfriend (Yes) and if he was Jewish (No). Why not? he asked. How about a Jewish man? Do you want to get married? (No.) Do you want to have children? (No.) I remember my chest flushing red. In a culture where a maximum of three dates arranged by a shadchan is the norm before deciding whether or not to wed, talking marriage is totally normal flirting, though our context was unusual. We were standing very close together, speaking a language few around us could understand, but touch was impossible when we both understood its implications, and so the conversation had nowhere else to go. We regarded one another for a long moment, then I dunked into the cold pool and abandoned our heat in its chill.

- There’s plenty of grounds to understand this as impulse as problematic, that I like much of mainstream white American Jewry was fetishizing, objectifying, and othering Hasidim, locating Jewish and Yiddish authenticity somewhere other than in myself. But in retrospect, and having learned a great deal from chaser discourse in my gay transsexual adult life, I think it was more complicated than that. My social location now, as a visible Yiddishist, means other Jews sometimes map expertise and authenticity onto me.

- See Mirjam Zajdoff's 2013 book Next Year in Marienbad: The Lost Worlds of Jewish Spa Culture, or just watch Dirty Dancing.

- Reading about the Jewish-gay-mafia affiliation of these bathhouses, I’m again reminded of Harrison Apple’s work on Pittsburgh’s after-hours gay clubs, and the ways in which mafia affiliation was crucial to providing protection from police raids so that gay sexual and social life actually had somewhere to happen.

- For more see Jane Ward’s Not Gay: Sex Between Straight White Men and C. Riley Snorton’s Nobody Is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low.

SINKHOLE / GLORYHOLE is free but if you have the money and inclination to pay for it, that would be cool. (I'm hoping to have Stripe paid subscription option set up soon, but for now, and thanks to a local reader for offering, you can tip me at @golus-goals on Venmo or $golusgoals on Cashapp if so desired.) As always you're invited to send tips, opinions, criticisms, and nudes to me, Dade Lemanski, at dadelemanski@gmail.com. More historically informed Rust Belt (and otherwise) sodomy news arriving in your inbox soon.